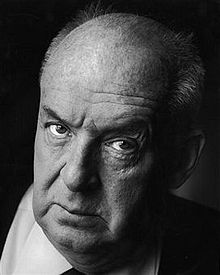

I’m reading James Wood’s How Fiction Works. It’s a great book, a useful book. Especially good is his section on ‘character’. Woods reports that Nabokov thought of his characters as chess pieces he could move about how he wanted. Nabokov was God in his own work. None of this vague magic about characters speaking to him, characters catching him by surprise with the amusing things they do, characters – oops – falling under buses. Nah, Nabokov was God, and there was no such thing as free will in his universe.

I’ve only published one book but I’ve already been asked a few times why I’ve written a main character who is male. I am female, so maybe it catches some people by surprise — all first books are autobiographical aren’t they?

Here’s a statement: All characters are the writer, in this or that guise.

This is not to say that all fiction is autobiographical. It is true that writers imagine characters and put them in imaginative situations; all this done in the context of a real, material world. (Even writers dealing in ‘other’ worlds and fantasy worlds must deal with the material and work doubly hard to convince their readers of the verity of their worlds). What I mean when I say that all characters are the writer is that the writer will bring to bear on her characters all her prejudices, politics, sense of humour, her vocabulary, her style.

This is what makes the best writers so wonderful, to my mind. I can read a Grace Paley story and know I’m going to get female characters who act tough but let us in on their vulnerabilities. I’m going to get a Grace Paley voice in my head whenever a character speaks and I’m going to get Grace Paley politics. She was a writer who cared about vulnerable people’s place in the world, a writer who would fight for them in her fiction (and her real life). That’s why I go back and read Paley, Austen, Knox and Gee over again – I want their voice (made material in the form of their characters) in my head for a time.

Characters are not people.

I’ve heard writers say that their characters are mixes of people they know – and I know from experience that I make my characters say funny and weird things I’ve overheard. Sometimes I give them facial tics that I’ve noticed in real people. But this does not make my characters people. I heard Elizabeth Knox being asked the question about how she can write males (how can she write angels for that matter?) and she said: they’re not male or female, they’re characters.

So if a character is not a person, what is it? A collection of words on a page. Yes, but if so, why would people still care about Elizabeth Bennett two hundred years after her creation if she were just words on a page?

Back to the master then: a character is a chess piece. Watch Nabokov make this early move with Humbert Humbert (HH) in Lolita:

‘Around me the splendid hotel Mirana revolved as a kind of private universe, a white-washed cosmos within the blue greater one that blazed out-side. From the pot-scrubber to the flannelled potentate, everybody liked me, everybody petted me. Elderly American ladies leaning on their canes listed toward me like towers of Pisa. Ruined Russian princesses who could not pay my father bought me expensive bonbons.’

This is a small detail, a minor piece in the description of HH’s early years, and a lead-up to his meeting with Lolita’s ‘precursor’. But what a minor piece! The cossetted, adored child who had everything he could possibly desire delivered to him on a silver plate. I especially love the picture of the American ladies, overstuffed and old, listing on their canes towards the golden child. Of course this child grew to be a man who could take whatever bonbon he desired. At the game of character, Nabokov was a world-class chess master.

Characters are chess pieces who can make a limited number of moves, depending on their mode of play.

The material that occurs to the writer when two characters start to speak and interact with each other is where this issue of control becomes interesting. It occurred to me the other day as I worked on a story involving a meeting between a farm-wife and a man who says he’s a minister of the church that these two character were not just meeting for the first time, they were old acquaintances. However, the situation they’re in means they must act as if they’re meeting for the first time. I had started to write the scene as if they didn’t know each other. I could not have come up with this idea of a prior relationship until I’d put them in a room together and made them talk. Who was in control when this idea occurred to me? It certainly didn’t feel to me like I was driving the characters especially hard at the time – at least I didn’t feel the mental strain I sometimes do when I’m pushing a scene forward. It was a pleasurable idea to have and more importantly, it opened up numerous possibilities for the story that weren’t present before.

I want to say that my imagination was in control. In the room in which these two characters met, governed by me, an ignition, a chemical reaction, was happening. I don’t understand it. I hate saying things like ‘my imagination was in control’ – what vague magic that is. What I do know, what I have learned to recognise, is that my idea was a good strategy towards an end-game. I could write on.

Another thing that Woods says in How Fiction Works is that ‘a great deal of nonsense is written every day about characters in fiction’.

Ahem.

Wood’s book will never leave my desk. The short section on point of view (together with Laurence Fearnley’s ‘Room’) about 3 weeks into the MA changed my (writing) life.

I’ll have to check out the Fearnley story, I don’t know it. Yes, Woods writing about free indirect style is brilliant, esp that piece he quotes from ‘What Maisie Knew’