A series of interviews with people about the work they do.

Kelly McDonald is a jeweller. She was born in Moe (which means ‘swamp’ in the Aboriginal language), in the Latrobe Valley, Gippsland, Australia. Kelly has lived in Wellington, New Zealand since 2004. She teaches jewellery at Whitireia New Zealand.

“There’s a T-shirt somebody got printed that sums it up. It says: ‘I’m not that sort of jeweller.”

–Kelly McDonald

Kelly McDonald in her shed

Interviewer

What are you doing?

Kelly McDonald

I’m cleaning up, because it’s part of my process.

Interviewer

Part of your process of what?

Kelly McDonald

Of making. If I’ve got a clean, clear space then my head is clear. You know, the internal mimics the external.

Interviewer

Do you think you’re a details person or a big picture person?

Kelly McDonald

I don’t know that I could answer that honestly. I’d have an idea about it but I don’t think it would be true, it would just be me saying what made me look better.

Interviewer

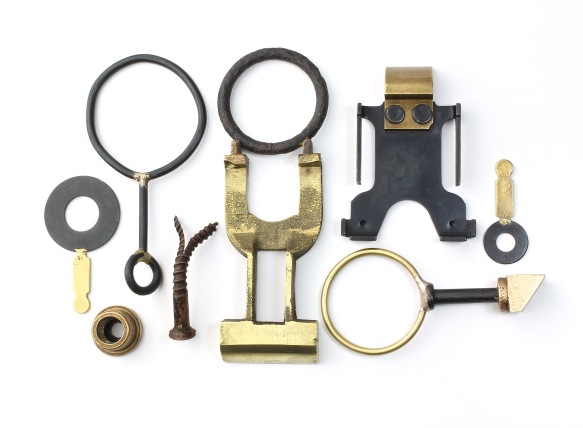

But here you’ve two large white sheets of paper with things laid out on it; if I stumbled across one of these objects on the footpath, I wouldn’t even notice it, and here you are arranging lots of bits of rusty metal, stones, and these things, floats from fishing nets, and you’ve arranged them and there’s a pattern and order to this.

Kelly McDonald

It would be true to say that this is the detail of a big install. These are visual clues for me; by laying them out I start to see that I need to make more of these and I’ll build it up.

Interviewer

Do you mean the pieces will be bigger or there will be more of these things?

Kelly McDonald

More of these things. In my work shed, and quite often in galleries, I’m limited by space because I don’t do many solo shows. I tend to do big group shows or small 2-3 person shows. I’m still getting started and the idea of a solo show is intimidating, plus I can learn more from group shows. But, I’m getting closer to the idea of wanting and needing a solo show. These pieces work better when they have more space around them.

Interviewer

So they have their own margins? Their own white space? Which is how I would think of it in publishing terms.

Kelly McDonald

Yeah. I’m starting to find jewellery a little bit limiting. I’m trying to work out why and I think it is the space thing. The body is really important for me in jewellery, which is why sculpture or small sculpture doesn’t really draw me in. It’s the relationship with the body and the scale that you have to work on that interests me.

Interviewer

Do you mean that people can wear these pieces on their body, or have you just made them a size that is in scale with a body?

Kelly McDonald

There’s lots of ways you can interact with the body that isn’t just wearing. That’s the financially viable form of making, but lucky for me I’m subsidised by my partner, and I work.

The relationship with the body can just be implied through weight. Like with those stones pieces—we have the knowledge about the weight of those without needing to explain.

The other thing is that I’m moving to not wanting to lock my work down, certainly not behind glass, so that when it’s displayed you can pick up the work and try it on.

Interviewer

So people should feel okay to take it off the wall and touch it and hold it?

Kelly McDonald

Yeah. And my work’s tough. I watch this British maker, David Clarke, who is a contemporary silversmith, and his work is always for touch rather than ‘Do Not Touch’. And every gallery has to be okay with that because that’s his way of exhibiting. When I first heard that I was like, ‘Oh yeah, whatever…’ But then I went to an exhibition of his last year and walked in to the gallery and the usual reverence you have for these objects and the ‘not touching’ wasn’t there, his irreverence and the freedom of being allowed to touch actually made his objects more intriguing.

Interviewer

Is reverence part of the preciousness of the materials?

Kelly McDonald

Yeah, but then his things are three to four thousand pound! They’re hollow form, so you drop them they’ll dent, but for him that’s part of it. That’s a piece starting its life already and it’s been made for touch.

Interviewer

So it’s made for the human body, for people. Do you see it as a communication form?

Kelly McDonald

I think so, and I think that’s what all artists do—we’re communicating something. But with painting, you just look at, you don’t touch it, and it has no relationship to the body through the hands at all, it’s only about eyes.

With jewellery more senses are involved because you wear it and it’s a constant interaction with the body; having to put it on, take it off. My work looks good on a wall because it’s flat and graphic, but I’m thinking more about where the body is in wall display.

I wonder if it’s a tension in my making, where I have to work through these conundrums? I don’t always have a solution and maybe I never will but it’s one of the things that drives me.

Interviewer

So it’s part of finding a form for a piece?

Kelly McDonald

That’s what I’m working out. I’ve been back making for three years. There’s parts of it that are exciting because they’re still new. Like knowing your process and playing with it.

Interviewer

With writing, there are things that really irritate me in certain texts. For instance, I can’t bear cleverness or people who need to show that they’ve read all the post-modern books. I will always choose story above that. I’ve gone back to reading children’s novels recently because they’re often pure story, and thinking about how they work has affected my own writing, it has put more restraints around how I write, because I’m not satisfied with something just because it makes me sound funny or smart, which I might have been ten years ago, but now, anything I say must be an integral part of storytelling.

Kelly McDonald

Yeah well, separate of anything we do, we have our own core values, and honesty is a really important one for me and it obviously is for you too. So in communicating directly and honestly you can do all those fancy things like set shiny stones in a ring, or for you, indicate how well read you are through language. I guess for me that thing of putting the work behind glass doesn’t feel honest, because it’s about the touch.

Interviewer

So your values give you a set of constraints to work within and one of those constraints is ‘I’m not going to use glass’.

Kelly McDonald

If I can choose to do that, then yeah.

Interviewer

You said you’ve just come back to making for 3 years. You took time off?

Kelly McDonald

Ten years, for children.

Interviewer

And in those years, did you feel frustrated? Or did you always know you’d get back to it?

Kelly McDonald

Ha! Well, I had that fancy dream that we all have with our first child, ‘I’m gonna have so much time, cause I won’t be in a full time job.’ It’s easy to imagine that, so I did.

Previous to having my first child I had been working in the film industry, which is a vortex you get sucked into and don’t always come out of. Then I had a second child, and I couldn’t do it with one, so I wasn’t able to do it with two, but for some reason when I had a third child suddenly you have that level of chaos and you just jam everything in, because you realise you’re running out of time and no one cares that much.

Interviewer

How old was your youngest when you started seriously getting into making again?

Kelly McDonald

He must have been one and a half.

Interviewer

In the time that you weren’t making, you were teaching?

Kelly McDonald

Yes, so I did stay connected. I was also part of ‘The See Here’, which is a very small gallery space in Tory Street in town. It’s not run by anyone, and you don’t enter the space, you just look through the window. With one show every year there, it kept me gently tethered to making.

I also joined up with a collective of like-minded women who were in similar positions with time constraints and we found we could do more as a group than we could do individually. We all have different skill sets—one can put an application in, one can start making the work, another can photograph it, the others can add their few bits and pieces, and before you know it, we’ve got a show. Collectively, we’ve been able to stay strongly tethered to jewellery, and also build the community in Wellington. It’s small here, but with a community you can keep growing things.

Interviewer

It sounds like a really supportive community.

Kelly McDonald

Yeah, it is.

Interviewer

I can’t imagine writers ever banding together in quite that way, perhaps it’s not possible. But jewellery does seem quite a solo pursuit, like writing. I guess you could share a studio space, or would that be too distracting?

Kelly McDonald

I’m too easily distracted, and distracting, so it’s better for everybody if I keep a separate space.

Interviewer

How long have you been making jewellery?

Kelly McDonald

I graduated from Sydney College of the Arts when I was 23 and I’m 42 now. It was a bachelor of visual arts, jewellery was my major.

Interviewer

So how did you know you wanted to make jewellery?

Kelly McDonald

I was ten and I decided I was going to be a nurse and a jeweller. I grew up in a small country town in Australia, and I was going to do my nursing degree at home in country Victoria at the local uni, then move to a city and study at arts school and pay my way through casual nursing, or agency nursing. And that’s what I did.

When I arrived in Sydney to start my course and find a place to live, at one of the flats I went to look at, I got talking to the woman and she said she ran a nursing agency. So I joined up with her agency within the first few days of getting to Sydney and was working within a week. I didn’t take that house but I got a job out of it.

Interviewer

That seems exceptionally driven and clear-minded.

Kelly McDonald

Yeah, that path was direct, but then it’s been much less direct ever since. Maybe the first ten years were all mapped out, but after that, no.

Interviewer

What gave you that kind of clarity? Did your family give you a model for it?

Kelly McDonald

No, not at all. But then, my father’s generation of men wasn’t encouraged to be creative through art, nor was it financially viable if you had a family. If you haven’t ever been exposed to art no matter how creative you are it’s hard to pursue. Dad is quite creative, certainly with metal, but his creativity comes through his job as a fitter and turner; his hobby is making and building motorbikes. I think that’s how that generation of man expressed creativity.

Interviewer

So if you didn’t have any artists in your family, what gave you the idea that you could be one?

Kelly McDonald

I liked making things as a kid; I was always making things. Mum suggested that I do jewellery. I liked little shiny things, so jewellery made sense. I couldn’t get an apprenticeship, so the other option was to go to university to learn it. As I got older the idea of arts school in a big city was really appealing.

Interviewer

What do you say you do when people ask?

Kelly McDonald

I’d probably say I’m a maker.

Interviewer

Why not a jeweller?

Kelly McDonald

‘Jewellery’ has lots of connotations and I always need to qualify that by saying I am a contemporary jeweller. And people ask, ‘What does that mean?’ and there’s a lot of explanation you have to give. Whereas if I say ‘I’m a maker’, that word carries its own weight and you can explain your materials and then say what you’re doing. Also, if you start with jewellery there’s usually a request to fix something or you get shown a diamond ring. And I don’t do stones, I have no interest in that kind of jewellery.

Interviewer

Why don’t you do stones?

Kelly McDonald

They just don’t appeal to me.

Interviewer

You’ve got a bunch of stones over there.

Kelly McDonald

Yeah, they’re pebbles. Beach stones, greywacke.

Other stones, they get cut and they’re not how you find them. I really like uncut stones, they have a beauty for me that is worthwhile, but the cut stones, I mean you can do that with glass as well, I don’t see the point.

Interviewer

You call yourself a maker but do you think of your work as jewellery?

Kelly McDonald

Only in that I belong to a jewellery community.

There’s a teeshirt somebody got printed that sums it up. It says: ‘I’m not that sort of jeweller.’

Interviewer

Is it because there’s not a public consciousness about what contemporary jewellery is?

Kelly McDonald

It’s growing. Wellington has the jewellery degree at Whitireia. I teach there, and we get small numbers, but every year we get five students at least and every year between two to five go through to second year. There’s growing numbers of people who want to look at contemporary jewellery and buy it. Certainly that’s the case in New Zealand. I wouldn’t say it’s so everywhere else in the world.

Interviewer

There’s people that collect jewellery the way they would collect art?

Kelly McDonald

Yeah, and there’s an awareness too, amongst jewellers, that we need to encourage young people to become collectors so there is an investment, there’s a building of the community. I think it will continue to grow it might just not grow in massive numbers very quickly. There’s a small number of people here, but we’re always represented in the major shows overseas.

Interviewer

Why do you think that is?

Kelly McDonald

I think our difference is interesting for people.

Interviewer

A difference to what?

Kelly McDonald

To the European aesthetic and their sets of rules. Europe is the seat of all things jewellery; there’s the largest number of jewellers there. What we do is so different to Europe—the way we express ourselves, our choice of materials, the things that we talk about with our jewellery.

Interviewer

Why do you think it’s different?

Kelly McDonald

Because we don’t have that weight of tradition on our shoulders; we don’t have this long history of how art has to be produced. We don’t have the guild system, we don’t have the hallmarking system, which is where if you want to sell or exhibit at certain places you have to send it off to be assayed then you have to apply all your hallmarking stamps. We don’t have lots of those systems.

Another thing that I see as quite different is that we don’t have a hierarchy of materials. It’s difficult to get stuff here. I had no idea, even in comparison to Sydney, where I could just ring up and have stuff on my door from the courier. But here the turn around is longer, so you make differently because you can’t get things or they’re a lot more expensive because there’s no large industry. It’s that geographic isolation at play.

Interviewer

I want to ask about the lack of guilding or standard system here. It’s fascinating because on one hand they might look at us and say, ‘Oh, they’ve got no standards’, but from what you’re saying, it actually creates more freedom.

Kelly McDonald

I think they’re both important, but the way people learn can be problematic. If you go to a traditional school, the expression of the work or the idea of the work is never put first, it’s only ever a consideration down the track or maybe not at all. This is not the way that we would think about an idea.

For example at that [a European] school you’d learn how to solder, and you’ll learn one way which is the ‘proper way’, the way that everybody has learned before, it’s the way that is financially viable and expected in a trade type jewellery shop, like Michael Hill. It’s very hard to undo that learning after and go back to freedom and a playful way of trying out new things when you already know how to solder; you can’t unknow that.

We often say that it’s like an accent, you can learn a new language but you’ll always have your accent. We show you lots of different ways of soldering, and that allows you to find your own individual way of doing this standard activity of soldering bits together. When you approach everything like that it’s a lot easier to find your own individual voice.

Interviewer

Do you have a favourite material?

Kelly McDonald

Steel, that’s been the most consistent material I’ve stuck with.

Interviewer

What’s the attraction of steel?

Kelly McDonald

It shows time. It’s a dynamic material; it takes heat in an entirely different way. Steel is a ferrous metal; all the non-ferrous metals are things like copper, brass, silver, gold. I see it as more flexible, although most people wouldn’t think of it as flexible, but when you’re making, and heat is a big part of your making process, when you can use heat in lots of different ways as opposed to one way, then that’s flexible to me.

Interviewer

So it responds differently?

Kelly McDonald

Yes. You can heat steel in one area and it doesn’t move very quickly, it doesn’t conduct in an even way like a non-ferrous metal, like copper and brass. This is why copper is used in lots of things; it conducts evenly. With steel, if you heat one corner the other corner doesn’t heat up so you can do a lot more with it, you can have cool spots and hot spots.

Interviewer

Is it unpredictable?

Kelly McDonald

Steels have different levels of carbon and iron. I mostly use mild steel. I don’t use stainless steel, or high-carbon steels, so I find it predictable, but there’s a million things I still don’t know about steel so for me it still holds new things that I can learn.

Interviewer

When did you discover steel?

Kelly McDonald

I didn’t use steel until I was in my last year of uni, and then I didn’t use it for a long time. But I do play with all sorts of materials. Steel works really well combined with other materials, you get that contrast, which keeps it interesting. The possibility of one colour with the black or greys that you get with steel… There’s also the movement and the way two materials marry—a non-ferrous metal will move around on steel, it’ll never join with it, so you can adhere it to it but it’s not like a weld of steel with steel. So that’s an exciting thing for me, at some point I’ll get a welder and do steel to steel. One day.

Interviewer

Do you call what you make art or craft?

Kelly McDonald

I think there’s crafting in what I do but I don’t think it’s craft. Craft has a different history, and I don’t feel like I’m talking that language. In my version of art, the artist shows a proven dedication over time. I’m new back to making and I think it’s going to take longer for me to talk about my work in relation to art, and about me as an artist.

Interviewer

Really? That’s interesting because while you didn’t make for a number of years, you’ve been doing it for a lot of your life, always heading in that direction. Do you mean that you think you must have sophisticated concepts before you can call yourself an artist?

Kelly McDonald

No. I think the sophistication comes with just going the distance; that being your mode of expression for a long time. After three years, I think I’d be presumptive to call myself an artist. I think that in five, six years, I’d be comfortable, maybe. You could ask me in another three years.

Interviewer

Do you feel like you’re still doing an apprenticeship?

Kelly McDonald

To some extent. The Handshake project has been fundamental in getting me back to making.

Interviewer

What’s that?

Kelly McDonald

It’s a mentor and exhibition programme funded by Creative New Zealand. It’s now in its third iteration. In Handshake One, there were 12 reasonably recent graduates and they selected a mentor anywhere in the world and the programme matched them up with that mentor and then they worked towards exhibitions with a certain amount of support from their mentor.

Interviewer

That’s a very innovative programme.

Kelly McDonald

Yeah, it’s unique. Internationally it’s being watched by the contemporary jewellery world through the blog sites. Each Handshake artist has a blog and posts their progress in relation to their exhibitions. We’re now at Handshake Three and possibly there will be a fourth, there’s a long commitment to it, which also keeps building that community, so the graduates coming through now know there’s something to go into.

It’s made a big difference in keeping me focused. Having external deadlines, which without I would have found it difficult to keep the motivation going.

Interviewer

What’s your star sign?

Kelly McDonald

Taurus.

Interviewer

Did you have any art influences as a child or young adult?

Kelly McDonald

I didn’t go to exhibitions; that’s just not what we did. We lived two hours out of Melbourne and we went to the city a few times a year. No doubt there were exhibitions happening locally, but it didn’t occur to mum and dad to take me, nor did it occur to me to ask to go. I went to my first exhibition when I was just finishing high school. It was a local painting show, and it might have even been part of our art class.

There was the Melbourne Show, which was an agricultural show, and throughout school you could make things for the Melbourne Show and I remember submitting something and I won a little award when I was 7 or 8, quite young, but that’s a stretch to call that exhibition experience.

Interviewer

And what about now—do you have other painters or sculptors that you love?

Kelly McDonald

There’s too many to choose from. I feel like I’m still new and until my voice is known as ‘Oh that’s hers’, I don’t want to talk about other artists. I’m still gathering bits from all sorts of places.

Actually, can you remove that question?

June 2016, interview by The Invisible Writer